Remebered and Retold - Life Story of the Otto Family

Chapter 5

High School Years

The time in the Kant Gymnasium passed without any great turmoil. We had no school uniforms, but each year we bought a different-colored cap with stripes designating what grade we were attending. We wore the caps with great pride. I hated the Latin class but enjoyed the Greek. As usual it was the teacher who made the difference. We had to learn the first two pages of Homer's "Odyssey" by heart in Greek. Memorizing poems and excerpts from literature was an everyday assignment. Standing in front of the class to recite a recently memorized poem required lots of concentration. Physical education was a blast. Who would not like volleyball, soccer, rowing, track and gymnastics? On the parallel bar as well as on the single bar we attained a respectable level of proficiency. Mathematics became one of my favorite subjects.

During the summer weekends the whole family paddled in a wooden three-seater kayak to the "Kaiser Wilhelm Turm." It was a picturesque tower on the Havel River about four miles south of Spandau. It had a nice beach with a 300 foot steep embankment from which one could view the one-and-a-half-mile wide Havel River with its hundreds of boats. The famous Grunewald started right behind the beach with its dense pine woods. My mother always prepared a picnic. I had to get her little stove going, on which she cooked fresh asparagus with veal cutlets. A fresh plum pie was the dessert. Hundreds of wasps plagued us when we tried to eat the pie. A man not far from us did not notice a wasp as he took a bite of a piece of pie. He was stung by the wasp deep inside of his throat. Within twenty minutes his throat became so swollen that he had difficulty to get air through his trachea. I watched my father perform an emergency tracheotomy with his pocketknife and save the patient's life.

In 1935 two Jewish couples who frequently joined us on these picnics already discussed their misgivings about the increasing anti-Jewish sentiment stirred up by the Hitler regime. In 1937 both of them emigrated to Chile.

My sister Gisela's and my grades in French were only at the "C" level. So, my mother looked in the newspaper ads to engage a French teacher who would come to the house once a week and practice conversational French with us. Mademoiselle Monique was in her mid-thirties. She wore heavy makeup, a custom German women did not or were not allowed to practice under Hitler. A strong perfume gave us teenagers an aura of a intoxication. She wore a fox stole around her neck which was held together with a safety pin. When she took her shoes off, a hole on each of the big toes in her stockings was obvious. She spoke only in French with us, trying to explain the unknown word to us with all kinds gesticulations. After several weeks we started to understand and enjoy her conversation better. She was very vivacious and covered all aspects of human life with her stories. She had us get a famous French love story book, which was quite juicy and helped to further my sex education. We were learning French in great strides with the "Adriane" book and the dictionary. Both our grades improved.

In 1934 an old patient of my father, a Mrs. Sieg -- who later married Arthur Zschischang -- visited us with her son. She lived with her husband in Buffalo, New York. Harro was older than I by half a year. Mrs. Sieg had traveled to Germany to place her son into a German school to avoid the bad influence the surroundings in Buffalo had had on Harro. Striptease joints, liquor, crime and gang war were not the right environment for a teenager to grow up in. She had read in the American press how the situation in Germany had changed for the better since Hitler. She intended to place Harro into the Napola, the National Political Educational Institute, in Potsdam. Since the new school year was to start within one month, my mother suggested that Harro could stay with us for that time. Harro moved in with me and we had a great time together until he had to get into the strict regimen of the military school environment. During his school year he spent the weekends at our home. He could not get out of uniform fast enough. He talked less and less with me, and I sensed that he hated the military school. He was very tight-lipped about his experience in Buffalo.. After six months he decided that he could not take any more restrictions and regimentation. I am sure he was homesick and was longing for Buffalo. But he did not write to his parents. On one Sunday Harro took 4000 marks out of my father's desk and did not show up in school the next day. When the school called to ask his whereabouts, he could not be found anywhere. After several days my father discovered the missing cash. We all assumed he was back on his way to the U.S. But why had he not spoken to my father? He would have given him the fare to return to the States. We did not hear from him or his mother for three months. Then a letter arrived from his mother stating that he had found a job on a farm in Brazil, where he wanted to stay for the present. Two years later his mother wrote that he had died of a sudden unknown illness. Of course, my father never pressed the Siegs to repay the money.

I had saved several hundred marks from all the gifts of relatives and money I had earned tutoring students in the lower grades in math. I bought a single-seater collapsible boat, and from then on paddled alone to join the weekly summer picnics. During the summer vacation I loaded the boat on a train to Saarbrücken to take a trip down the Saar River. The population of the Saarland had just voted to return to Germany and the people celebrated the end of the separation. Visitors were welcomed with open arms. The Saar River with its gentle current was ideal for a kayak adventure. After arriving in the city, I put my folded up boat, which was packaged in two separate bags, on a small two-wheel collapsible carriage and pulled it three miles through the streets to reach a spot where I could assemble my boat on the riverbank. A dozen children followed me to see what I was dragging behind me and watched the assembling of the boat. I felt like the "Pied Piper of Hameln." The intricate assembling of a folding boat was new to my little audience. First, I spread out all the different parts of the boat on the embankment. It took me more than an hour of hard work and sweat until my pretty kayak with its blue bottom and orange deck was ready to be launched. A tent, rain gear and food supply found easy room inside the boat. The collapsible boat carriage followed the rest of the gear. With a great send-off by the young crowd I finally pushed off into the river and let the current carry me down the winding stream among the steep hills planted with grapevines. After each bend in the river a little village emerged with the villagers waving at me, wishing me a "Gute Reise". I slowly drifted into the sunset and started looking for a camping place. I found a meadow to put up my tent and spent the first night all by myself with the river current and its gurgling noise lulling me to sleep. The birds woke me up at dawn. After a cup of coffee and a hearty breakfast I collected my belongings and pushed the boat back into the river. I soon drifted towards Trier where the Saar joins the Moselle. A tour of the 2000-year old Roman city, where Emperor Charlemagne was crowned, was my first pleasant interruption. The river at that time had no locks or floodgates and moved along with a three-to-four miles per hour current. As soon as I entered the Moselle River, other kayaks joined me. We went down the Moselle valley with its many turns, vineyards growing on every hill and small villages every three to four miles. Our kayak family had grown to twelve boats by now. A romantic trip down the Moselle attracted many kayak fans. As usual, I was the youngest as I had been through all my school years. We camped every night at one of the villages made famous by its wine. Being only fifteen years old, I had to taste the golden liquid in every village with a more and more relaxed happy kayak group. Kayaks were a novelty at that time on the Moselle. The enterprising townspeople sent out the baker in the morning to the campground to offer his still warm crisp rolls. The town's butcher followed him, not to miss his chance to get in on the business. In the evening we ate frequently in the local inn of the village and tried the best wine, which could be had for one to two marks. It took over two weeks to make it all the way to Koblenz. Our group had grown in the meantime to fifteen boats and all or us had a marvelous time enjoying the lovely Moselle River. We stopped at the famous "German Eck," the confluence of the Rhine and Moselle. I had to say good-bye to my newly won friends since they all stopped their trip at that spot.

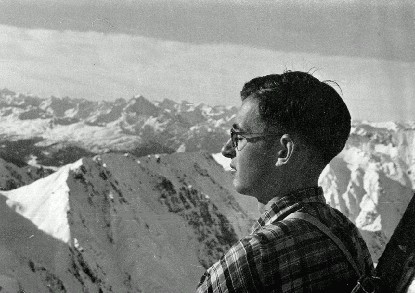

Jürgen

Otto on a skiing

vacation in 1938

When I entered the Rhine, a swift current of nine miles per hour took me past many castles and famous wine villages. Boats were steaming upstream pulling as many as six barges. Passenger boats were passing by with music and songs coming over the water to me. When I went by the "Lorelei cliff," I realized that Cologne was only a few more miles down the river. It had taken only two days from Koblenz to join my aunt and uncle in the famous city. They received me with great relief since they had heard nothing for three weeks from the fifteen-year-old adventurer.

The next summer vacation I repeated this romantic experience. I sent my collapsible boat to Lichtenfels, a small town on the Main River, which was just big enough for a kayak to float. I hiked first to the Fichtelgebirge, a mountain range where the Main River starts as a small spring. From there I marched several days along the spring until it became a creek and started as a small river in Lichtenfels. Here I picked up my boat, and after three weeks I ended my trip near Frankfurt in Hofheim in the Taunus mountain, where another aunt welcomed me.

My father financed a trip to America for my older sister in 1935. It was with a feeling of jealousy that I helped send Gisela off. America in 1935 was a distant continent, mystic, unknown and daring. It took at least seven days to get there by boat. A group of German students was gathered in Berlin to accept the invitation of La Guardia, the mayor of New York. Gisela also started the connection with my father's cousin in New York, Aunt Frances. In the German paper I read about the reception the students received from the mayor and the sight-seeing trips they had been offered.

Not to shortchange me, my father asked me in the summer of 1937 whether I wanted to join some older friends to make a trip to Paris. The World Exposition was the great attraction at that time. I had to bring several certificates and affidavits stating that I was no enemy of the Third Reich before I received permission to travel to Paris. What a surprise it was for me to read the French press and its opinion about the Third Reich! It was the first time I could observe Hitler's Germany from the outside. The Olympiad was twelve months behind us, and I had thought that this was the greatest accomplishment of the new regime. I expected to hear only praise of what Germany had done so far. But the press was full of criticism and concern. For the first time, I realized that I was living under a dictatorial regime. For three days we haunted all the pavilions of the World Exposition and took in the sights of Paris and Versailles. On the last day we went to visit a bordello where naked girls gave us a show, since we did not want to participate in their offered service. I had to be careful after my return not to divulge the opinions I had read in the foreign press about our regime at home.

It was customary at sixteen to enter a ballroom dancing class. My mother bought me a new suit and tie, inspected me carefully and sprinkled some eau de cologne on my hair. Gisela told me not to be shy or hesitant during the first lesson, but to look all the girls over and ask the nicest looking and prettiest one to be my partner in the first lesson. While all my classmates where standing around before the class started, I picked a lovely blond girl and ask her whether she was willing to share the first lesson with me. Her name was Ruth Gross. She came from the girls' school to which my sister also went and wanted to be a doctor. Of course, after three more lessons I fell in love with her. I walked with her many miles through the Grunewald holding hands and discussing mainly school matters. We remained good friends until the end of school and then both of us went different ways.

Gisela finished her Abitur, the qualifying exam for entrance to a university in 1937. To be able to start her university education, she first had to enlist in the "Arbeitsdienst," Hitler's labor service. She was assigned to one of the poorest regions of Germany, sixty miles south of Berlin, where she had to help a farmer's wife with their children. They ate bread soaked in flax oil made from the local grain. The other food was also very poor. In camp where the girls stayed overnight they were fed mainly soups which gave them all round, puffed-up faces. My sister suggested that I should visit the labor camp during a weekend. My father promised to let me drive the Mercedes, so I loaded up the car with all kinds of good food and sweets and took off. At seventeen and the only male the girls had seen for weeks, I made quite a splash. Discovering my car full of food, they asked me to come back again the next weekend.

My"Abitur" approached in the spring of 1938. This meant fourteen different examinations, each lasting five hours each. It took almost three months to get through all the written examinations. The knowledge acquired during nine years of schooling was demanded for the Abitur, not just the last year's learning. During my final math examination I was finished in less than three hours with the test. I was rechecking all the results once more when suddenly three rolled-up wads of paper fell on my desk with questions about the results. The math teacher, a man of small stature, was sitting with his chair on top of the desk. It was dangerous to return the paper wads. I returned one of them to the student who had given me a sign with his blinking eyes. Then I asked the teacher for permission to go to the bathroom, because I wanted to deposit the rolled-up paper in a predetermined hiding place. Of course, this was an old trick known to the teacher. "Puppy," as we called the math teacher, made a fast trip after me to the bathroom and found the paper wads. All hell broke loose.

"To whom did you intend to give these results?" he asked me over and over again. Even after fifteen minutes of questioning I would not divulge the name of the classmate who had thrown the question to me.

"Don't worry. I will find out later. All students who had a 'Fünf = failed' during the last semester and come up with correct answers will have to figure the problems on the blackboard during our next class. I will find out who can solve the problems without help. Otto, you are not mature enough to pass the Abitur," he shouted at me, enraged.

This normally very nice teacher turned out to be really cruel and mean. He had even recommended me as tutor of his math students who had an "F" in the lower classes. I reported the incident to my father, who had a different opinion. Not to inform on your classmates showed more character than turning in their names. He went with me to the school principal and argued his case more or less successfully. In the negotiated compromise I had to redo the math examination alone in the principal's office. In the meantime I got together with the two "F" students who had received my wads of paper. I worked with them for hours until they were able to solve the problems on the blackboard the next day. My heart beat so hard that I was afraid the teacher could hear it whd loads of sacks with rice imported from India, where mice had found a way into the sacks. The first few weeks we had a detail to pick mouse droppings out of the rice. The rice was then cooked with onions and a few pieces of mutton. We had to pick up the meals from the kitchen tent with our German aluminum containers for breakfast, lunch and dinner. After one month we discontinued the search for the mouse droppings and cooked the rice the way we got it. I felt that the mouse excrement's were not harmful if the food was adequately cooked. The excrement dissolved completely during cooking and did not affect the taste.

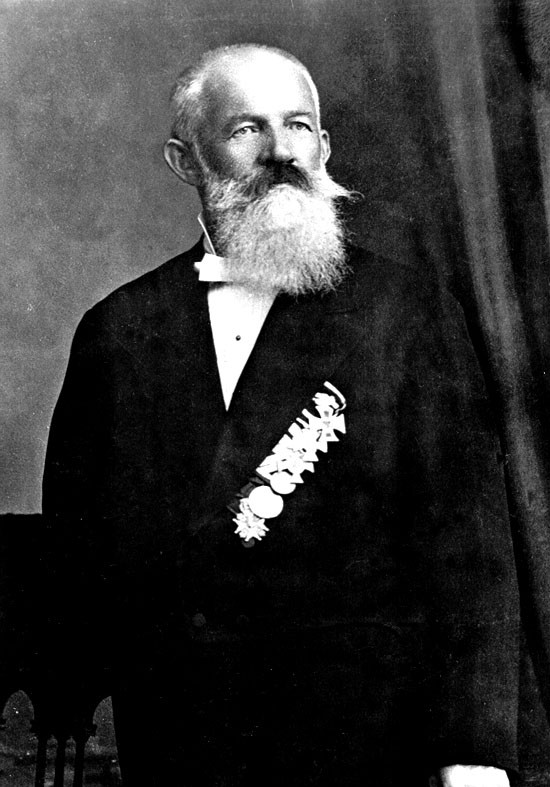

Gottfried Friedrich Otto, Jürgen’s Grandfather

After two months we each received a one-page Red Cross letter which permitted us to inform our next of kin that we were still alive. To kill the long days of idleness, we got hold of some cardboard and made chess boards out of them. We cut our chess figures with homemade scissors and were ready to start endless matches. At least half of us learned the game if we did not know it before. Some of us developed great skill in the game and could play with six players at the same time and win most of the games. Very popular was a race with the large carpenter ants which populated our camp. We dug runways in the sand and started to race the ants by putting a small piece of a cracker at the goal. The smokers among us suffered particularly since there were no cigarettes during the first two months. After several weeks somebody got the idea of starting a choir. We practiced daily for two weeks and had a substantial repertoire of well-known erman folk songs and Christmas carols ready for performance. Whenever there were English soldiers outside the barbed-wire area, the choir started a concert for the enemy who seemed to enjoy it. As a reward for the singing, the English would throw half-smoked cigarettes into the compound, where the prisoners carefully re-rolled them in newspaper and smoked. After two months we received the first cigarette ration of one pack ofen the three students had to solve the problems on the blackboard in front of the class. I had done a good job. To the amazement of "Puppy" they solved the problems.

Three days later I found myself in the principal's office for this special examination which was supposed to be my penalty. I worked very hard to solve the much more difficult problems the math teacher had given me this time. I had tried to memorize all the different formulas, but some of them were too difficult to recall. Previously I had looked them up in my math book. The principal sat straight across from me at his desk and telephoned constantly while I was struggling with the test. I had a small piece of paper with the formulas pasted on the inside of my tie to help me with the formulas one normally has to look up in the book. I had to rest the tie on his desk to read them. The grade I received was again a straight "A." Since I was a B+ student and had no "Failed" or "C's" in any of the classes, they had to pass me. This ended my high school years with a rather dramatic but finally happy end.

© Irmgard

& Jürgen Otto 1993 All

rights reserved